The Hopp Children’s Cancer Center Heidelberg (KiTZ) is a joint institution of the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg University Hospital (UKHD) and the University of Heidelberg (Uni HD).

the area of the adrenal glands or along the spine in the neck, chest or abdomen. A distinctive feature of neuroblastomas is their extremely variable disease course: In some cases, the tumor regresses completely without any therapy. In about half of the patients, however, even highly intensive therapy cannot prevent aggressive growth.

However, there is currently no internationally recognized uniform method to reliably distinguish high-risk patients from those with a favorable disease course already at initial diagnosis.

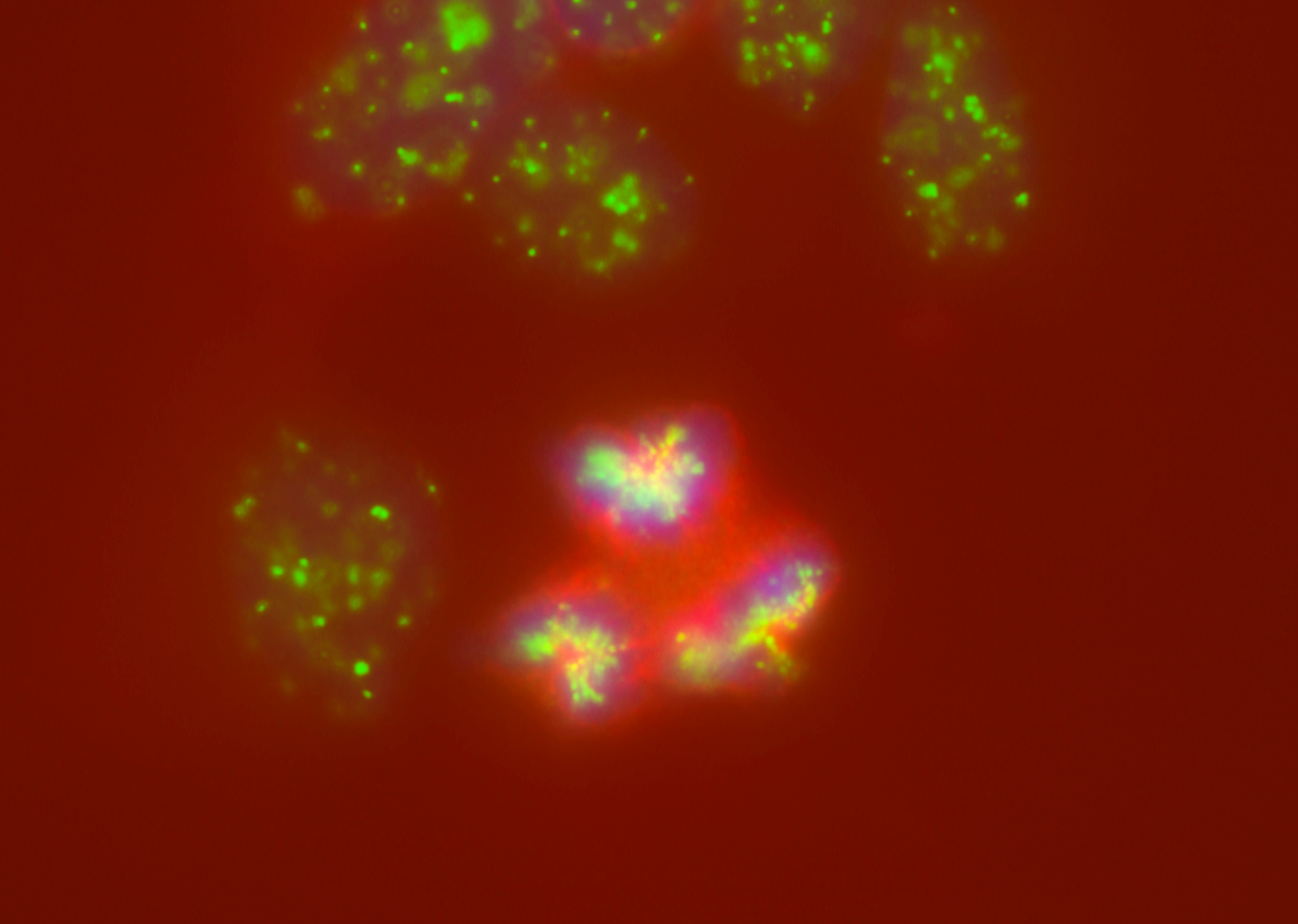

"Until now, it was assumed that these were completely different neuroblastoma diseases," says Thomas Höfer of the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ). The team led by research group leaders Höfer and Frank Westermann from the Hopp Children's Cancer Center Heidelberg (KiTZ) and DKFZ has now been able to show for the first time that both neuroblastomas from high-risk patients and those with a favorable disease course have a common cellular origin. Already in embryonic development during the first third of pregnancy, cell division starts to get out of control and already there the course is set for a favorable or aggressive course in children, the present study shows.

For this purpose, the scientists decoded the tumor genome of 100 patients with neuroblastomas of different stages. They then reconstructed the genesis of the tumors on the basis of specific genetic alterations. "It is assumed that genetic changes in our genome accumulate randomly and over time at a constant rate like sand in an hourglass," explains the study's first author Verena Körber from Thomas Höfer's Theoretical Systems Biology group at DKFZ. "This is also called a molecular clock and can be measured. With the help of a specially developed mathematical model, we were able to reconstruct a family tree of neuroblastoma development from this," Körber continues.

The family tree shows at what point the cancer cells take very different developmental paths and which genetic events are decisive for this. By correlating the results with the clinical course, the scientists were able to divide neuroblastomas into two categories: Those in which genetic alterations lead to tumor growth early on. "Paradoxically, these are the tumors with a favorable course, even if they initially grow faster. But drastic genetic events no longer take place, giving the cancer cells the tools to become immortal in the long term," explains Frank Westermann, an expert in childhood neuroblastoma at KiTZ and DKFZ. "They are also usually detected earlier in children because of their early rapid growth."

The second category is neuroblastomas that become malignant later but then grow aggressively. They undergo a more complex and protracted evolution. Thomas Höfer sees the reasons for this in the fact that, due to the cell environment or internal genetic damage, most of these neuroblastoma cells die: "Due to this selection pressure, however, they then develop particularly aggressive mechanisms to permanently escape cell death and remain infinitely active in division. Until that happens, however, the tumors remain small for the time being and are therefore unfortunately diagnosed later."

Mathematical models of cancer evolution are also currently being researched in adult oncology in order to predict the course of disease in leukemias, for example.

In children with neuroblastoma, they could help distinguish young high-risk patients from children who don't need therapy at all, the research team hopes. "We are currently working to establish tumor evolution as a reliable biomarker in neuroblastoma," Westermann says. "Ideally, such an analysis would then take only about three weeks after sample collection to provide an individualized therapy recommendation."

Original publication

Körber, V. et al. Neuroblastoma arises in early fetal

development and its evolutionary duration predicts outcome. In: Nature Genetics (Online Publikation March 27, 2023) DOI: 10.1038/s41588-023-01332-y